- Here we present the highlights from a recent Biostime Nutrition webinar with guest speaker Dr Ed Giles. Dr Giles is a consultant paediatric gastroenterologist at Monash Children’s Hospital and Royal Children’s Hospital. His research interests are in the field of mucosal immunology, particularly related to paediatrics and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- Dr Ed Giles received a speaker honorarium from Biostime® Nutrition. This Summary was written by Professor Peter SW Davies, Honorary Professor of Childhood Nutrition, University of Queensland. Professor Davies received a writing honorarium from Biostime® Nutrition.

Humans have consumed live bacteria in foods for thousands of years.1 Such foods, including yoghurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, and cheese, show widespread geographic and cultural consumption. The recent emergence of commercially available isolated live bacteria, probiotics, has led to an increase in live bacteria consumption, with rates doubling in the United states between 2002 and 2012.1,2 Publications relating to the effect and/or modification by probiotics of the gut microbiome have risen exponentially in recent years.3

Although more research is required to clarify the most effective probiotics for any given disease or situation.4 For example, health benefits shown for one strain may not occur with others, and there are even differences within species.4 Here we discuss some aspects of the relationships between probiotics and health and disease.

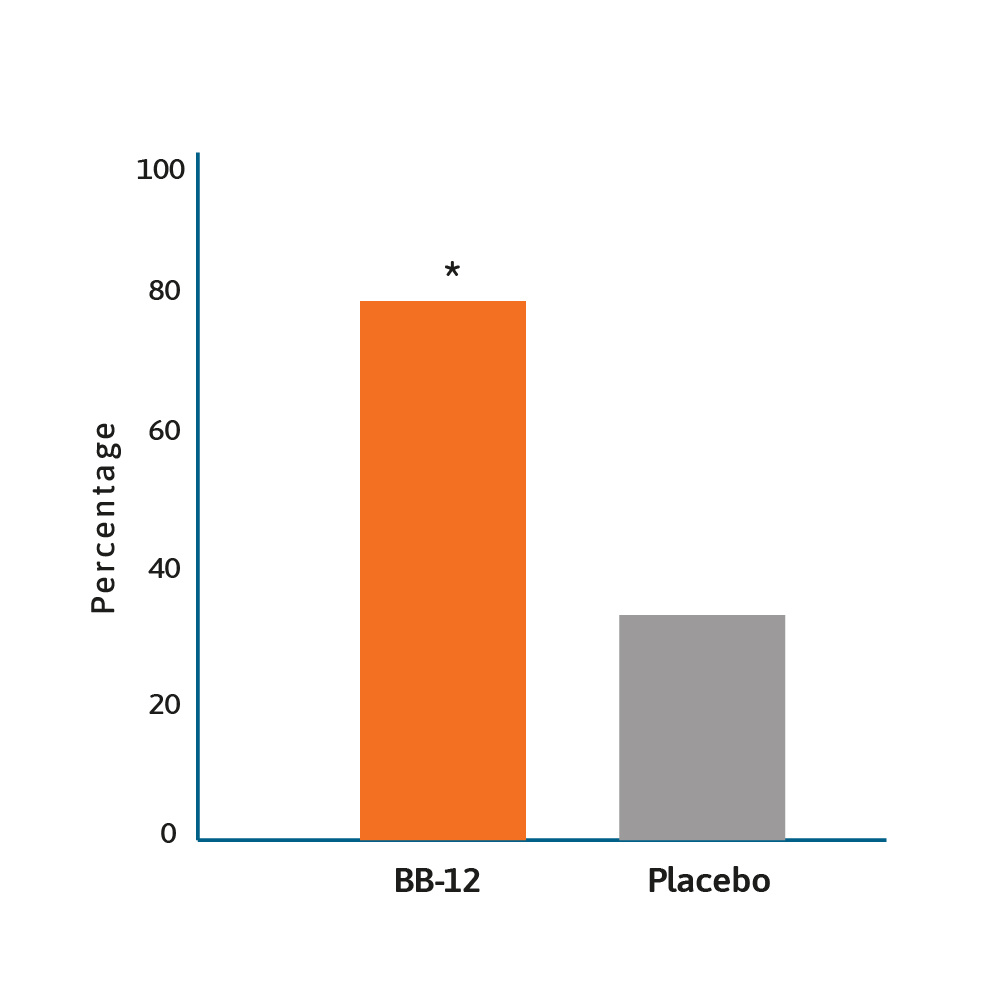

Rate of infants with ≥50% reduction of duration of

crying after 28 days of treatment.12

* BB-12 vs placebo, p<0.0001.

The work of Wessel and colleagues back in 1954, described colic as being associated with paroxysmal fussing in infancy.5 Over 60 years later, the aetiology of colic remains unresolved and there are limited treatment options.6

One treatment option that has been investigated in recent years is the role that probiotics may play in reducing fussiness and/or crying in infants with colic. This approach is based on the hypothesis that disturbances in the microbiota-gut-brain axis may be involved in the aetiology of the condition.7,8 A randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial showed that, based on parental reports, the median crying time of infants given the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938, reduced from 370 to 35 minutes a day, over a 3 week period.9

The same probiotic was associated with less crying when compared to placebo (38 vs 71 minutes per day; p<0.01) in infants after 3 months.10 This probiotic was also shown to have an economic impact, with an estimated mean saving per patient of ~US$120, with an additional US$140 for the community. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that not all the literature supports the use of Lactobacillus reuteri as an intervention for colic. In an Australian randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, one month intervention with Lactobacillus reuteri did not show any benefit in breast fed and formula fed infants with colic.11 Additional research is required, with a 2020 trial suggesting that Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis BB-12 is effective in managing infant colic via the modulation of gut microbiota structure and function.12

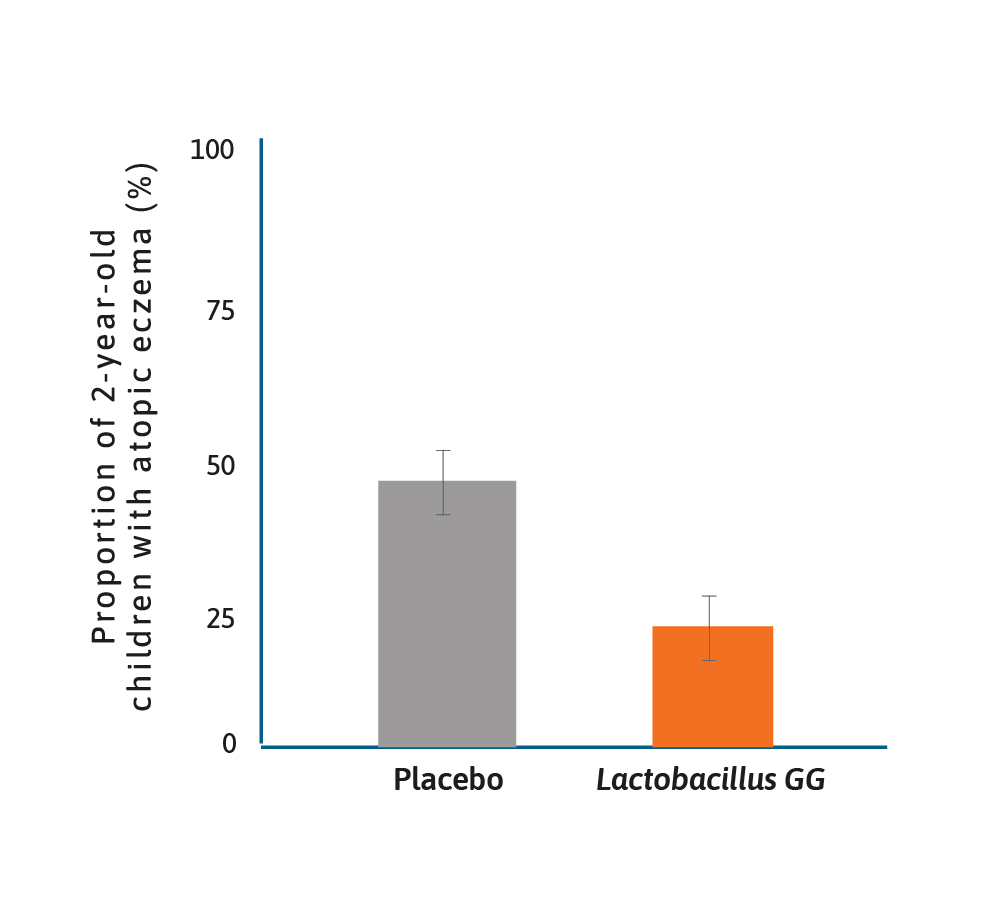

Treatment effect of Lactobacillus GG on atopic disease.13

It has long been suspected that there may be a role for probiotics in preventing allergy, notably atopic disease and eczema. One of the earliest studies was of Lactobacillus GG given prenatally to mothers with a family history of atopic disease and postnatally to their offspring for 6 months.13

In this randomised placebo-controlled trial (RCT), the frequency of atopic eczema in the probiotic group was half that found in the placebo group (23% vs 46%) and relative risk of 0.51 (95% CI 0.32–0.84). Since then numerous studies have shown benefits to infants in terms of eczema prevention, using either single probiotics or a probiotic mix.14–16 Although a recent publication by Wickens and colleagues suggested that maternal supplementation alone did not result in protection against eczema and that infant supplementation was important.17

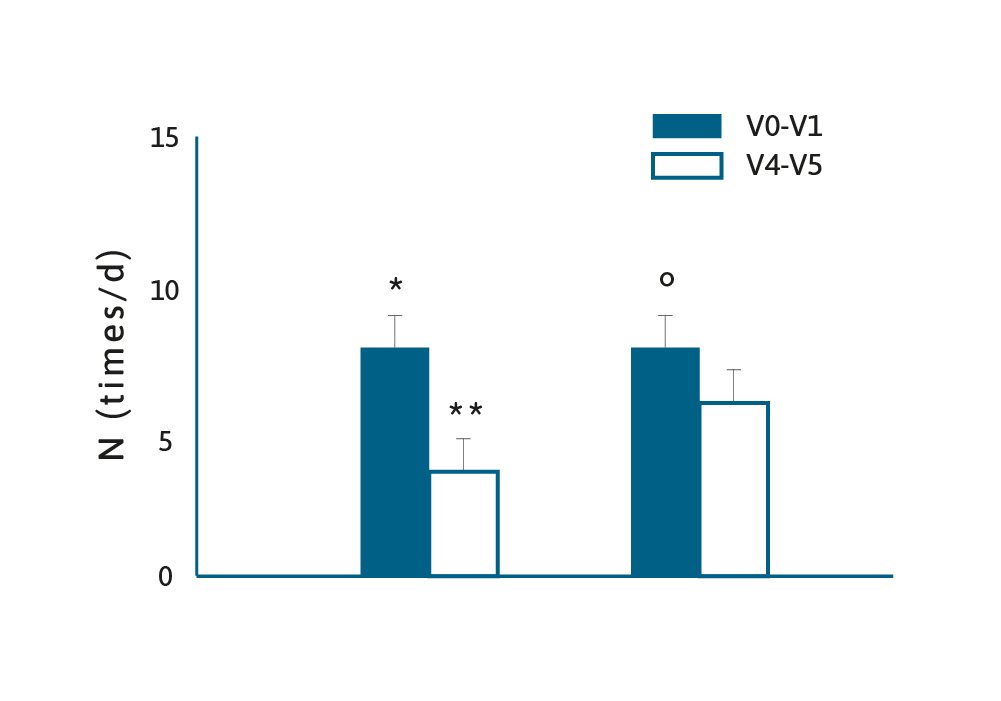

A systematic review and meta-analysis in 2016 examined the efficacy of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 (L. reuteri) in the management of diarrhoeal disease in children.18 Several studies showed that probiotics have both therapeutic and preventative effects in children with diarrhoeal diseases, however, there is a need to examine strain specific effects.18

A total of eight RCTs were included and the authors concluded that the administration of L. reuteri reduced the duration of diarrhoea, however, in a preventative setting the findings were mixed, with one study showing benefits, and another showing less convincing evidence. Studies that have evaluated the effects of probiotics on acute diarrhoea in children have produced contradictory findings. For example, a review of the potential benefits of Saccharomyces boulardii concluded this fungal probiotic reduced the mean duration of diarrhoea by ~20 hours.19 Which contrasts with a 2020 RCT of children with acute gastroenteritis who were given Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus helveticus or placebo.20 The authors concluded their data did not support routine probiotic administration in children with acute gastroenteritis. These conflicting results lend weight to the philosophy that “not all probiotics are equal”. 18 There is a well-established relationship between the effect of antibiotics on the existing microbiota, which can result in antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD), and the administration of probiotics may help restore the gut microflora.21

There was a recent Cochrane Database systematic review of 23 studies using probiotics in AAD, comprising nearly 4000 participants.22 Different probiotic strains were used in these studies, but overall the incidence of AAD in the probiotic group was 8%, compared to 19% in the control group (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.35-0.61). However, not all studies confirmed a beneficial effect. One study showed no effect of Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 9848 (LP299V) on AAD, or the incidence of abdominal symptoms in a RCT in over 400 children aged 1–11 years.23

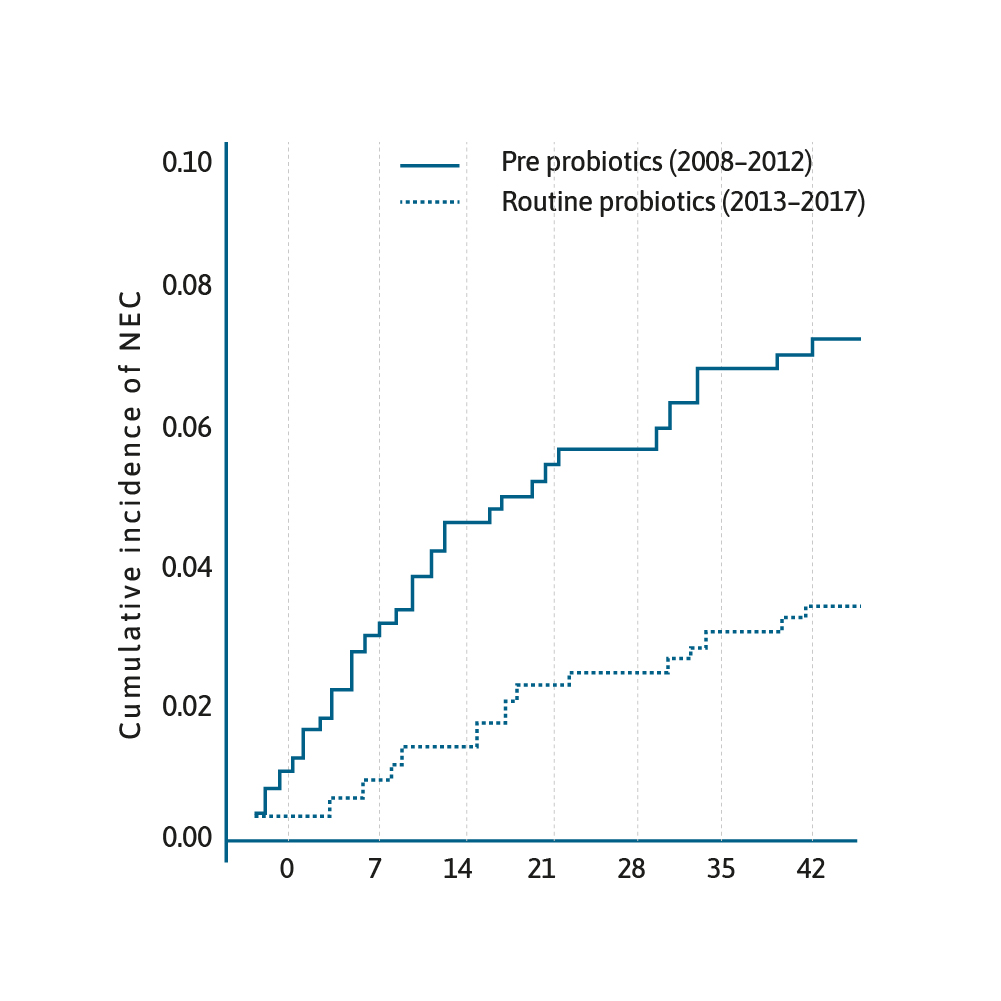

Cumulative incidence of NEC from date of birth stratified by epoch.29

The use of probiotics in preterm infants is an area of burgeoning interest. There have been several RCTs, meta-analyses and systematic reviews that have shown that prophylactic probiotics prevent necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in preterm infants.24–26

A meta-analysis published in 2017 of 25 RCTs, involving over 7000 neonates, revealed evidence supporting the use of multi-species probiotics to reduce the incidence of NEC (OR=0.36, 95% CI 0.24–0.53, p<0.00001).27 This has led to the question why has this cost-effective practice of administering prophylactic probiotics not been universally adopted.28

One reason may be that the evidence is still lacking relating to the optimal treatment strategy relating to both dose and strain of probiotic to use.30 This is a rapidly evolving area of research, a recent position paper by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition and ESPGHAN Working Group for Probiotics and Prebiotics, offered a measured, conditional recommendation, with low level of certainty. Providing that all safety issues are met, giving either L. rhamnosus GG ATCC53103 or a combination of B. infantis Bb-02, B. lactis Bb-12 and Str. Thermophilus TH-4 could reduce rates of NEC.31

In recent years, probiotics have been suggested as a treatment for many conditions including obesity32, mastistis33, respiratory infections34–35 urinary tract infections36 and more. While there is promise in these areas, at this stage there is insufficient data to make robust conclusions or recommendations, particularly realting to specific strains and dose to administer.4,30

Clearly this is an exciting and expanding area, but much is still to be understood.3,4 As discussed and highlighted here the main benefits from probiotic administration at the moment seems to be in the prevention of atopy13–17 and NEC in preterm infants.24–26.

Humans have consumed live bacteria in foods for thousands of years. Such foods, including yoghurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, and cheese, show widespread geographic and cultural consumption. The recent emergence of commercially available isolated live bacteria, probiotics, has led to an increase in live bacteria consumption, with rates doubling in the United states between 2002 and 2012. Publications relating to the effect and/or modification by probiotics of the gut microbiome have risen exponentially in recent years.

- Cohen PA. JAMA Internal Medicine 2018;178(12)1577–8 .

- Kantor ED et al, JAMA 2016;316(14):1464–74 .

- Hojsak I, et al. Acta Paediatr 2018;107:927–37 .

- Sanders ME. et al. Nutrition Bulletin 2018;43:212–5 .

- Wessel M, et al. Pediatrics 1954;14:421 .

- Partty A and Kalliomaki M. Acta Paediatr 2017;106:528–9 .

- Dubios N and Gregory K. Biol Res Nursing 2016;18:307–15 .

- O’Mahony SM, et al Pain 2017;158(4. Suppl 1): S19–28 .

- Savino F, et al. Pediatrics 2010;125:E526–33 .

- Indrio F, et al. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168(3):228–33 .

- Sung V, et al. BMJ 2014;348:g2107 .

- Nocerino R, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:110–20 .

- Kalliomaki M, et al. Lancet 2001;357:1076–9 .

- Wickens K, et al. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018;29:808–14 .

- Pedlan P, et al. Allergy 2017;72(Suppl 1):16 .

- Kim JY, et al. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010;21:E386–93 .

- Wickens K, et al. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018;29:296–302 .

- Urbanska M, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:1025–34 .

- Feizizadeh S, et al. Pediatrics 2014;134:e176–91 .

- Freedman SB, et al. Nature Communications 2020;11:2533 .

- Korpela K, et al. Nature Communications 2016;7:10410 .

- Goldenberg JZ, et al. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2015; Issue 12.CD004827 .

- Olek A, et al. Journal of Pediatrics 2017;186:82–6 .

- Al Faleh K and Anabrees J. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:506–14 .

- Olsen R, et al. Neonatology 2016;109:105–12 .

- Dermyshi E, et al. Neonatology 2017;112:9–23 .

- Chang H-Y, et al. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171579 .

- Vermeulen MJ, et al. Acta Paediatrica 2019.DOI:10.1111/apa.14976 .

- Robertson C, et al. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2019;0:F1–7 .

- van den Akker CHP, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;67(1):103–22 .

- van den Akker CHP, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;70(5):664–80 .

- Castaneda-Marquez AC, et al. Obes Res Clin Pract 2020; Doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2020.04.005 .

- Hurtado JA, et al. Breastfeeding Medicine 2017:12(4):202–9 .

- Emre IE, et al. Beneficial Microbes 11;3:201–11 .

- Laursen RP and Hojsak I. Euro J Peds 2018;177:979–94 .

- Hosseini M, et al. J Pediatr Urol 2017;13:581–91 .

Are you a Healthcare Professional?

Important Notice and Declaration

Breast milk is best for babies. Professional advice should be followed before using an infant formula. Introducing partial bottle feeding could negatively affect breast feeding. Good maternal nutrition is important for breast feeding and reversing a decision not to breast feed may be difficult. Infant formula should always be used as directed. Proper use of an infant formula is important to the health of the infant. Social and financial implications should be considered when selecting a method of feeding.

The information provided on this website is intended for use by healthcare professionals only. It is a condition of use of this site that you are a healthcare professional within the meaning of regulations within your country of practice. Then denoting below Yes I am/No icons. For Healthcare Professionals based in Australia : It is a condition of use of this site that you are a healthcare professional within the meaning of the Marketing in Australia of Infant Formulas (MAIF) Agreement or the Therapeutic Goods Act.